Leigh Bowery’s life was a one-act show—shock was his medium, and he took it as far as he could. Along the way, he found an audience: people who felt, thought, and behaved like him. People who challenged normality, broke taboos, and made expression their focus. Together, they formed a clan.

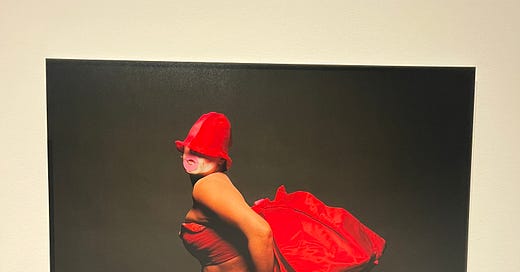

Sexuality was an easy way to provoke. It shocked then, and it shocks now. Bowery blurred the lines between genders, embraced fluidity, and exaggerated sexual forms—sometimes camp, sometimes grotesque, always impossible to ignore. In his early years especially, he played with these ideas as a way to upend convention.

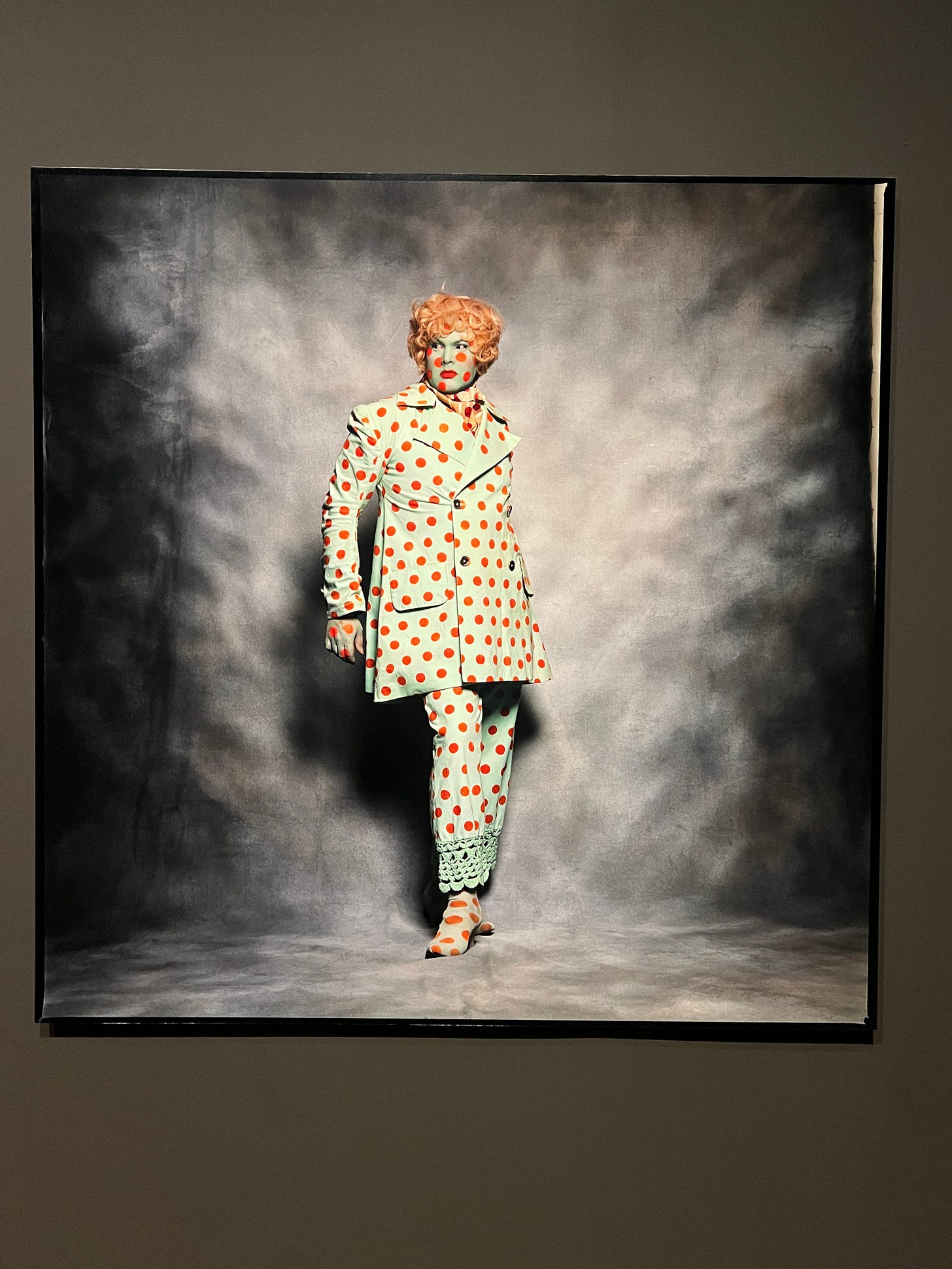

Then came the clothes. He was obsessed with the unseen, the untried. His creativity knew no limits, pushing boundaries while simultaneously drawing from tradition. He found inspiration in floral motifs, geometric patterns, and the saris of Indian and Bangladeshi communities in East London. But he never merely borrowed—he transformed.

His headwear, often covering his entire face, left only his eyes and lips exposed. He became a creature, his features concealed beneath layers of makeup. He swore by wearing makeup every day. But why did he cover his head? Was it influenced by traditional head coverings in East London? Did he want to remove the personal self from his creations? That seems unlikely—he craved attention, after all, and his boldness was never in doubt. Perhaps he simply saw his body as a canvas, from head to toe.

Seeing his work makes me think about clothing itself. We all navigate comfort, beauty, and self-expression. Some conform, some experiment, and some—like Bowery—push the limits of possibility. He pushed it to an extreme. His work wasn’t everyone’s cup of tea, but that was never the point.

Was what he created beautiful? Maybe not. Was it tacky? Definitely. Elegant? Unlikely. But it was striking, fun, and unapologetically challenging.

Bowery was fearless. He didn’t just perform on stage; he performed on the streets. He was visible. He demanded attention.

What drove him? Was it ego? A mission? Or was it simply about having fun, amusing himself and his friends?

One thing is certain—he had good friends. He surrounded himself with fellow creatives, not just joining a clan but elevating it, becoming a key figure, a symbol, an ambassador. His note about Trojan (Troj), written years after his friend’s death, is telling:

“Five years on, he is so alive in my head that if someone were to put different weights in my hand, I’d be able to say which one was the weight of his hand.”

Bowery collaborated with ballet-trained dancer Michael Clark, became the muse of artists like Lucian Freud and photographer Fergus Greer. These encounters, he said, helped him discover himself. He wasn’t just an object in art—he was an active participant in making it.

Was he a drag performer? Yes, but he was more than that.

He was relentless. The more attention he got, the further he pushed. He turned encounters into opportunities. His rise wasn’t accidental—it was systematic, built step by step. Success breeds success, and he understood that.

Was it art? Judge for yourself. What is art, anyway? Did Bowery inspire you? Did he make you think? There is form, and there is content—so it must be art.

Would he have imagined this life, this recognition, before arriving in London from Melbourne? He was born in 1961 and died in 1994.

Well done, Tate Modern, for this brilliant documentation of Leigh Bowery’s remarkable legacy. Leigh Bowery Exhibition at Tate Modern will run until the end of August.

Hurol Inan - London

Again, a though provoking piece. Certainly makes me want to see the exhibition

Another excellent piece about a person I would not otherwise have come across.